By: Nick Drainey

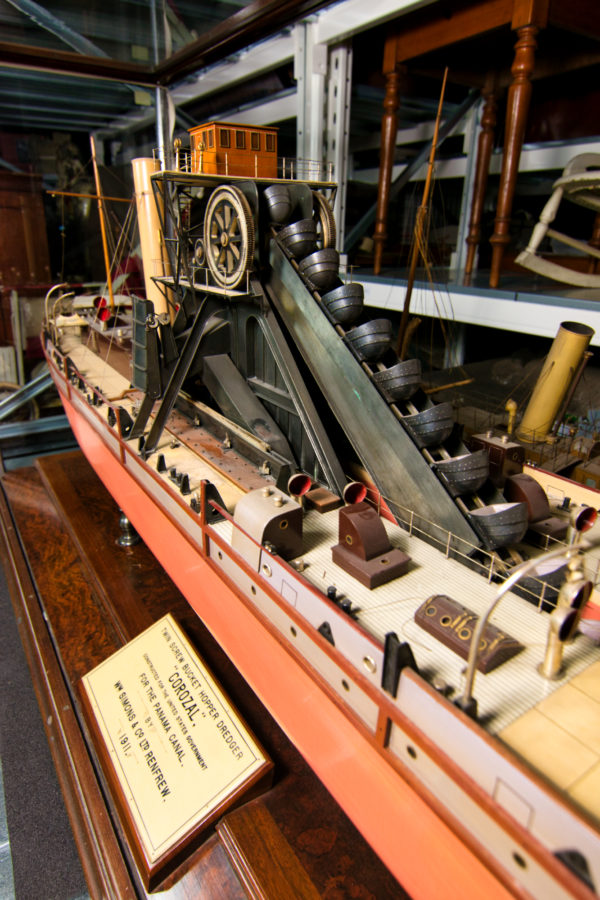

Paisley Museum has unearthed the incredible story of a Scottish dredger which built the last part of the Panama Canal and its Master from the Clyde. The Corozal was the only non-American machinery which worked on the canal more than 100 years ago, as Nick Drainey explains.

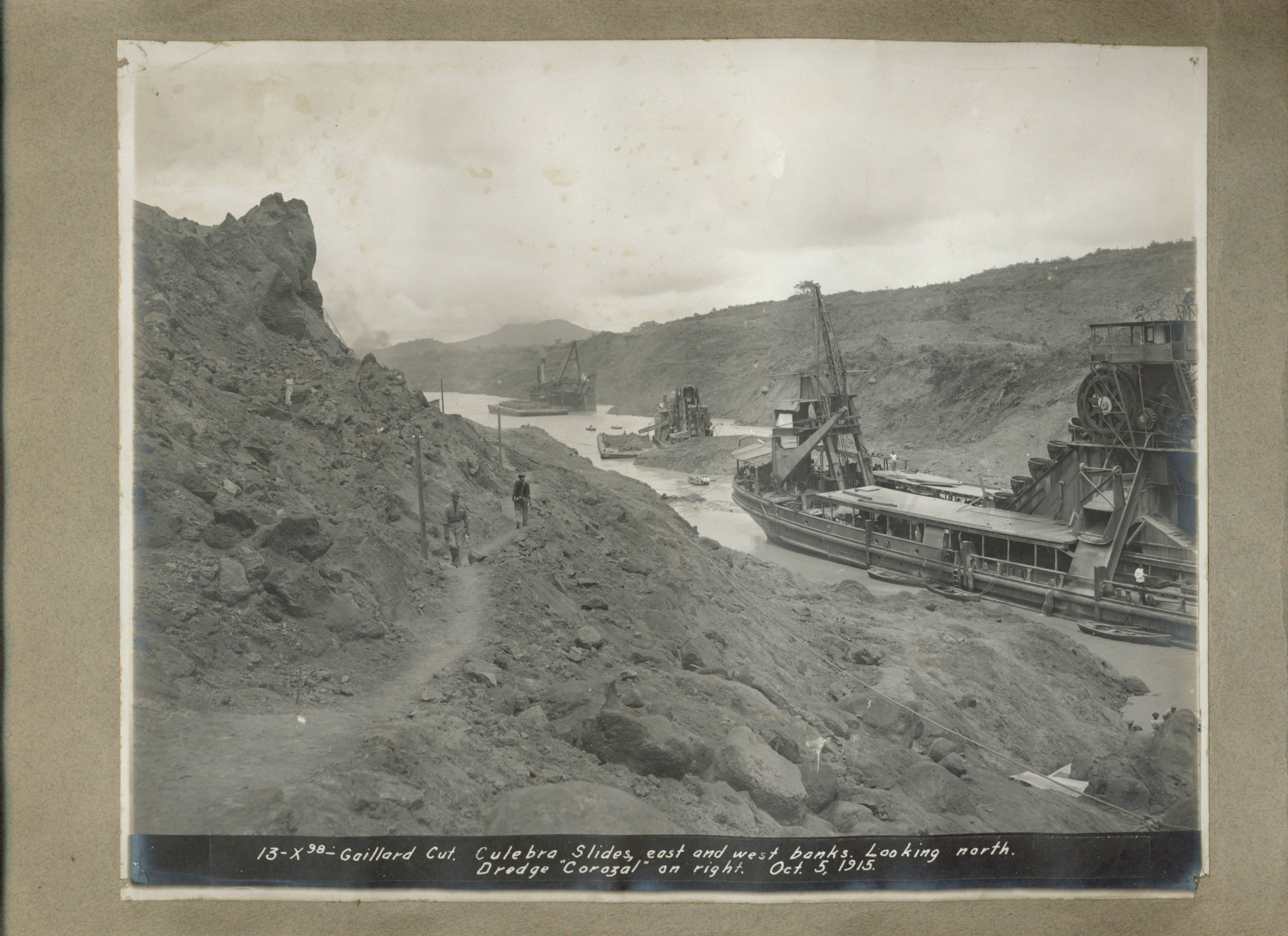

The forgotten story of a Scottish dredger and its master who sailed to the Pacific Ocean in the face of diplomatic unrest more than century ago and completed the final, difficult section of the Panama Canal has been unearthed during a multi-million revamp of one of Scotland’s oldest museums. In 1912 James Bartholomew Wallace sailed the Corozal from Simons shipyard in Renfrew, around the treacherous Cape Horn to the west side of Panama. Once there, it shifted more than 4 million cubic metres of earth from the Culebra Cut, the 12km channel on the final section of the canal as it meets the Pacific.

Despite fierce disapproval from San Francisco shipbuilders who wanted only US machinery used, President William Taft had awarded the contract for the work to the Scottish Corozal because he saw it as better value for money (just under US$400,000 compared to US$874,000). The story of how James Wallace overcame arduous seas, a tough working environment and opposition is to be told when Paisley Museum, Scotland’s first municipal museum dating back to 1871, re-opens next year after a £42million revamp. In preparing for the major refurbishment the museum discovered a model of the Corozal and decided to do some investigating.

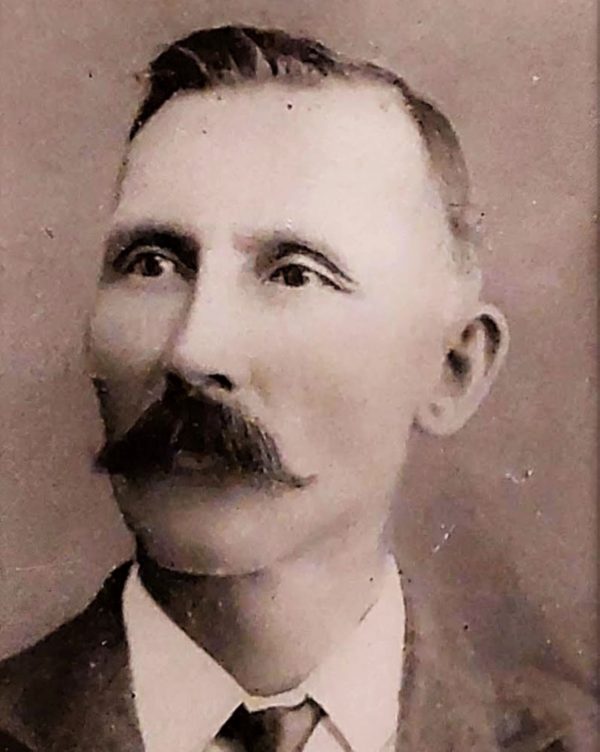

Shipbuilding family

Born into a Clyde shipbuilding family in 1870 in Renfrew, Wallace left school at 14 and began a five-year apprenticeship at Simons, a move that would eventually take him across the world. His first major voyage, in 1891, took him to the Pacific Coast of Mexico, via the Atlantic and Cape Horn. If that sounds a long way from home, it was but for many of that generation it was a chance to escape the confines of the yards. Wallace’s great grandson, Andy Wallace, who has made a long-term donation of family correspondence and photographs to Paisley Museum says: “He was from a shipbuilding family – he would have been an excited young man. That was their ticket to see the world and make some money.”

See the world he did, taking dredgers to Russia, China, India, Malaysia and Aden. Andy Wallace adds: “It does seem from his letters that every time he lands home he is off again.”

But Andy Wallace says his ancestor’s strong Christian faith was always central to his life, coupled with a “get up and go spirit”. And he did find time to marry Margaret Reid Phillips in Renfrew, Renfrewshire, on 24 December 1897 when he was 27 years old, and the couple had five children.

Held in high esteem

Meanwhile, 18,000 workers were toiling on the Panama Canal, hundreds perishing in the harsh conditions. William Taft had used his presidential powers to overturn a ruling by Congress that all future machinery should be US-built and had awarded Simons a contract to supply the Corozal. It was one of the largest dredgers ever seen at 261 feet in length and weighing 1684 tons. With James Wallace as Master, it set sail at the end of 1911, arriving in March the following year after travelling 12,000 miles during 117 days at sea. It was an impressive sight, dwarfing the other dredgers struggling to finish the final part – the Culebra Cut. By 1913 the canal was finished with the Corozal being the first vessel to pass through the final section before it was officially opened in 1914.

John Pressley, Science Curator at Paisley Museum says Wallace “must have been held in reasonably high esteem”, who says his name was included in a roll call of the senior workers on the canal. Pressley said: “He would have taken the dredger over there and spend three or six months handing it over to whoever was going to be operating it.”

The Corozal went to work out of Philadelphia and was eventually scrapped in 1956. James Wallace had returned to Scotland but then went back to Panama, where he died in 1915, aged just 44. Andy Wallace says the details are sketchy and he has never found a death certificate although he does know he is buried in the country. Wallace’s son became a marine engineer and his grandson, Andy’s father, was a diplomat. Andy Wallace is currently retraining as a marine biologist. He sees his great grandfather’s legacy as one of a “family who goes around the world doing what needs to be done”

The Clyde

In the 17th century the River Clyde at Glasgow was a shallow body of water which could be waded across at low tide. Ocean-going ships had to load and unload at Greenock with sailing up to the city an impossibility.

By the 18th century the trade in tobacco and sugar was booming and merchants wanted to be able to get their wares into the heart of Glasgow. A huge engineering project began which would see more than 100,000 tonnes of sediment dredged out. In the 19th century steam power created a revolution in production and shipbuilding on the Clyde took off, eventually seeing an estimated 25,000 vessels built on the banks of the river.

The shipyards played a vital role during the two world wars of the 20th century but decline began in the 1960s until today when they are all but gone. Nevertheless, the industrial heritage is still a source of great pride in all the communities along the Clyde, and it echoes around the world.

Paisley Museum

Paisley Museum was the first municipal museum built in Scotland, designed by renowned Glasgow architect Sir John Honeyman and gifted to the town by Sir Peter Coats of the Coats family, whose Paisley-based thread-making empire stretched around the world. Paisley was thriving at the turn of the 19th century thanks to the textiles industry and there was a real climate for self-improvement and intellectual curiosity growing in the town. Countless clubs and societies had sprung up, and there was a thirst for knowledge amongst the population. One such club was the Paisley Philosophical Institution which promoted education through its public lectures on a wide range of topics. They also collected scientific apparatus, objects, artefacts and books, and by 1864 were in need of a permanent home for their collection.

In 1864 they decided to launch a campaign to raise the funds needed to build a free public library and museum, and by 1867 had confirmation from Sir Peter Coats that he would pay for its construction. Paisley Museum was opened to the public in April 1871.The first curator, Morris Young, was an entomologist specialising in the study of beetles – his collection of over 2,000 beetle specimens is still held by the museum. Within 10 years of the Museum opening, plans to expand the galleries and build an Observatory were already underway. And, in 1883 what is now Scotland’s oldest Observatory was opened. Today, Paisley Museum is undergoing further redevelopment to improve the display of a vast range of artefacts including world-famous textiles, ceramics, over 800 paintings, sculpture, and local archives.

Main photo: Culebra Cut with Corozal on right, October 5, 1915. Photo: George W. Goethals Collection, Special Collections, USMA Library.

This was such a wonderful story. I read it twice and forwarded it on to many “Zonians” (Americans who grew up in the American Canal Zone” at the Panama Canal.

I drove by Corozal weekly over a period of 30 years, and would also work and shop at the U.S. Military Exchange (PX)

I often wondered where the name Corozal came from, as it was such a unique yet odd name.

I am so grateful for this wonderful article and journey of the amazing men who helped build the greatest waterway.

I could only imagine how incredible it would have been to have lived during this time.

Very respectfully,

Erik Petroni

(Son of Captain Gerard Petroni, Panama Canal Ships Pilot)