Seventy-five years ago this month on Christmas Day in 1950 four Scottish university students plotted to steal the historic Stone of Destiny from Westminster Abbey in London and return it to Scotland. The daring heist made worldwide headlines, and it is now housed again in Scotland, but some of the stone may have journeyed far greater as Judy Vickers explains.

When a policeman caught a couple canoodling in their Ford Anglia outside Westminster Abbey in the early hours of Christmas Day 75 years ago, he was inclined to be indulgent. After all, the pair told him they’d just arrived from Scotland and hadn’t been able to find a hotel – and who could resist a “no room at the inn” story at Christmas? The incident sums up all the key parts of the tale of the theft of the Stone of Destiny – hiding in plain sight, events going very far from plan and the making of a legend which is still giving up its secrets today.

Because the couple in the car were Ian Hamilton and Kay Matheson, two of the four Glasgow University students who carried out the notorious heist of the ancient Scottish coronation stone, seized by the English in the 1300s. The other two, Gavin Vernon and Alan Stuart, were at that moment hiding behind the jemmied door of the abbey – and a chunk of the Stone was lying on the back seat of the car.

Scottish nationalism

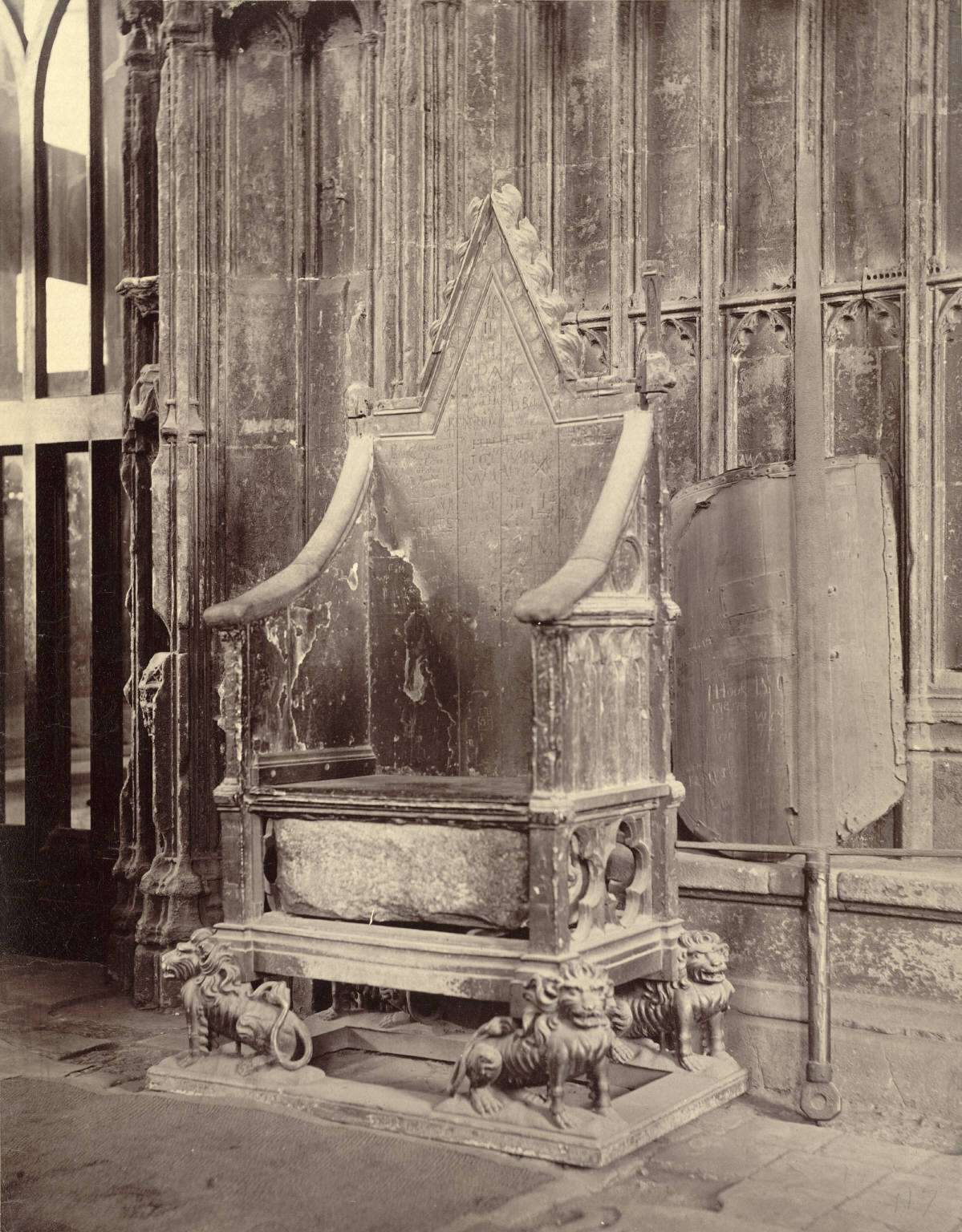

The four had arrived in London on December 22, 1950, with the idea of taking the Stone to highlight the cause of Scottish nationalism. All four were members of the Scottish Covenant Association, which was campaigning for a Scottish Parliament. And the iconic Stone was an ideal target – used in coronation of Scottish kings for centuries before being looted by the English king Edward I, known as the “hammer of the Scots”, it was housed at the bottom of a coronation throne built specially for the purpose in the abbey.

Firstly, Hamilton had hidden in the abbey at closing time, with the idea of letting the others in when all was quiet, but he was caught and thrown out by the nightwatchman. The next night, Vernon and Stuart were also foiled. In the early hours of Christmas Day morning, they tried a different tack.

The three men jemmied a door, managed to get inside and freed the stone from the throne but to their horror, the heavy block broke in two as they tried to drag it to the door. Hamilton grabbed the smaller piece of stone – still a hefty 40kg – and scarpered.

As he was heading for the car parked nearby, though, Matheson, the getaway driver, spotted the policeman approaching. “I drew the car in as closely as I could and Ian quickly pushed the stone into the back seat of the car and threw a coat over it,” she said later. Moved on by the officer, the couple drove off with the piece of Stone still concealed.

Stuart and Vernon fled the abbey but Hamilton – who would later be a contributor to the Scottish Banner – returned and lugged the chunkier piece of Stone out of the abbey by himself. He also found the keys to the second Anglia on the floor of the dark abbey – they had fallen out of his coat pocket earlier. He took the larger piece of stone to Kent where it was buried with the idea it would be returned to Scotland once the inevitable furore calmed down. Matheson took the smaller piece to a friend’s house. Hours later, when the theft was discovered, pandemonium broke out.

Myths

There are plenty of myths about the origins of the Stone – one that it was the Biblical Jacob’s pillow and came to Scotland from the Holy Land; another that it came from Egypt, brought by an Egyptian princess, Scota; yet another that it is actually part of the Irish Lia Fáil – also known as the Stone of Destiny – that the High King of Ireland had lent to the ancient Scottish kingdom of Dalraida, who never given it back. And in fact, Irish nationalists had attempted to steal the Stone in 1884. Modern tests show that it is probably hewn from stone local to Scone – but then that just adds to the legend that Edward was in fact palmed off with a fake. Certainly, many medieval descriptions of the Stone don’t match its modern appearance. But wherever it came from – and whether the 66cm by 41cm by 28cm sandstone block with an iron ring on each end was the original object that at least 42 Scottish kings used in their coronation – its seizure from Westminster Abbey was big news. For the first time in 400 years the border between Scotland and England was closed as the hunt began.

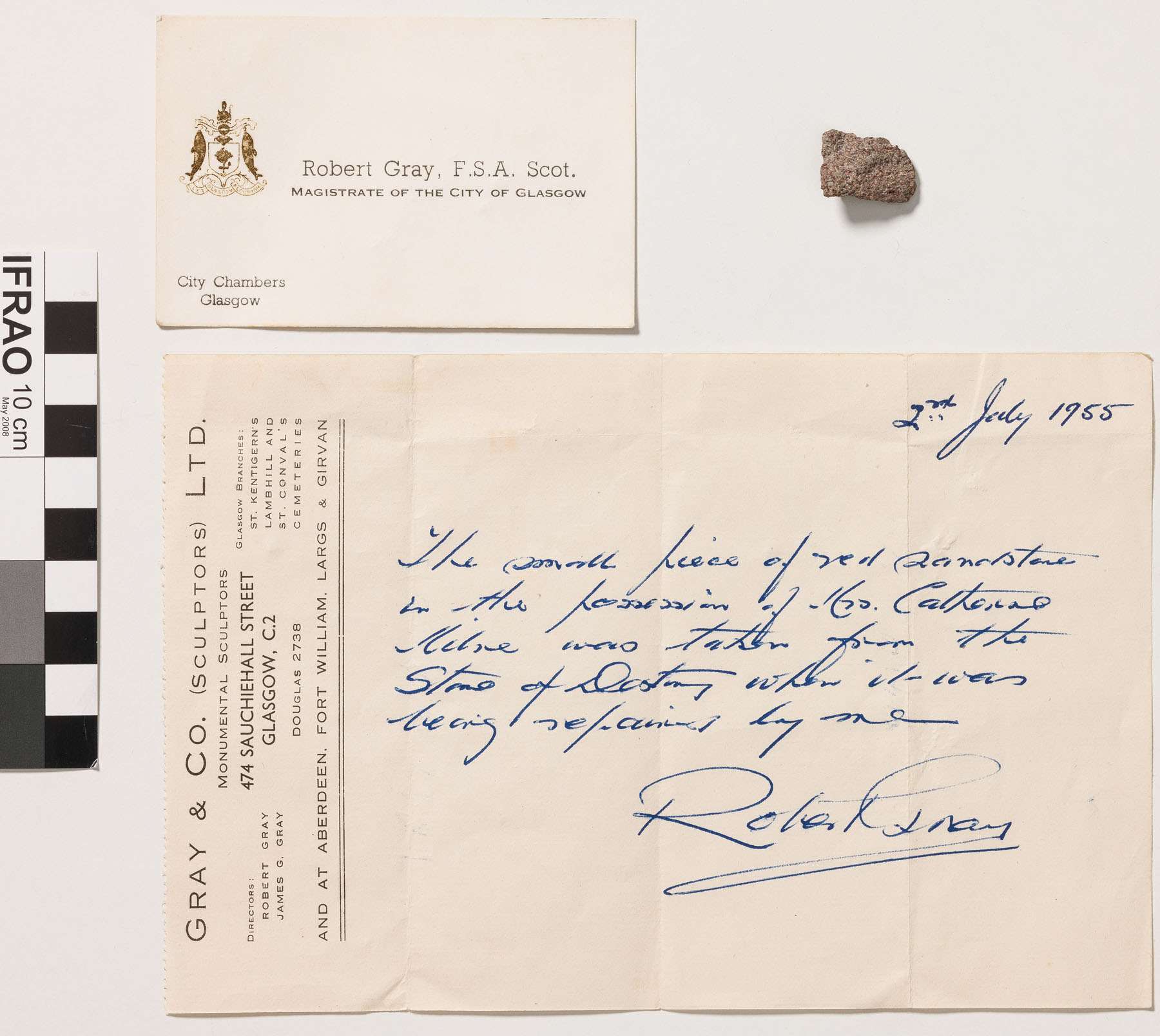

The students managed to get the two pieces of Stone back to Scotland where stonemason Robert Gray joined the two pieces back together with metal dowels. Already the myth was that the dowels were hollow and that Gray placed a message in one but just last month another twist emerged. Professor Sally Foster, of the University of Stirling, revealed research showing that Gray gave 34 fragments of the Stone away. Back in early 1951, detectives were closing in on the students – they had discovered that Ian Hamilton had taken out every book on the Stone from the Mitchell Library in Glasgow – so feeling they had made their point, in the April the students left the Stone at Arbroath Abbey, draped in a Scottish flag.

Returned to Scotland

The Stone was returned to London – ironically driven out of Glasgow Central Police Office in a Jaguar in full view which the waiting press ignored as they assumed it was a ruse. There it remained in a vault until it was used during the coronation of Elizabeth II in 1953.

On the 700th anniversary of its theft from Scotland, the Stone was officially returned. Now it is housed in Perth Museum, after having journeyed to London for a brief visit for the coronation of King Charles III in 2023. It still attracts controversy – in July a 35-year-old man from Sydney was arrested and charged with malicious mischief after an alleged hammer attack on the glass case containing the Stone, which was undamaged.

None of the students were ever charged over the theft – the authorities feeling perhaps wisely that they would be in a lose-lose situation with a guilty or not guilty verdict making the foursome either martyrs or heroes. And there would be the tricky matter of having to prove ownership of the Stone. Hamilton, who went on to become a lawyer, said: “I’ve defended a lot of daft people during 30 years as a criminal lawyer, but I doubt very much if I’ve defended anyone who was as daft as we were then.

Global Stone of Destiny fragments

Just last month there was a new twist in the tale of the Stone. Professor Sally Foster, of the University of Stirling, revealed research showing that Robert Gray, the stonemason who had repaired the Stone when it was left in two pieces after the students’ heist, had taken 34 fragments, chipped off as part of his repairs which he gave away as gifts. Only one was officially recognised when she began her research, but she has been on the trail of the rest – and has also discovered there are slivers of stone other than those taken in 1951. More than that, she says some have definitely travelled worldwide – including one which was last heard of in Canada – and she’d be keen to hear from anyone who can help her with her investigations. She told the Scottish Banner: “Yes, there are, and are likely, fragments outside Scotland dating from the 1951 repair, and other periods. I know of some examples which also travelled with people on their holidays to show to people, or when they migrated.” Several of the fragments were distributed to Scottish politicians, including former First Minister Alex Salmond, but one was gifted to a visiting Australian tourist by Gray. On her death in 1967, the family donated the fragment, accompanying letter of authentication and Gray’s business card, to Queensland Museum.

Another ended up in Canada. Prof Foster says: “Journalist Dick Sanburn received numbered fragment 25 in April 1951 – it ended up behind his desk as editor of Calgary Herald. I’d love to know what happened to it after that!” And she added: “From public responses since 17 Jan 2025, I know that tiny, tiny fragments and grains of the Stone (sweepings, even) were collected by another person present at the repair. Some of these have ended up with families presently in Canada and Norway, some mounted in jewellery. The 1951 fragments might have been given predominantly to people who lived in Scotland from 1951 to 1974 (the period in which we know Gray distributed them), but they moved, or the people to whom they donated them have moved. I don’t yet have a full picture of what happened to all the numbered, nor indeed unnumbered fragments, but I would anticipate that some of their journeys have been global, and a concentration within the Scottish diaspora is inherently likely.”

If you have any information on any Stone of Destiny fragments, you can get in touch with Prof Foster via the contact page at https://thestone.stir.ac.uk/.

Main photo: Stone of Destiny. Photo: © Historic Environment Scotland.

Support the Scottish Banner! To donate to assist with production of our publication and website visit: The Scottish Banner