In a thrilling quest to uncover secrets from one of Scotland’s most significant historical sites, archaeologists and volunteers will again partake in a remarkable dig at Culloden Battlefield, where the course of British, European and world history changed dramatically nearly 280 years ago. Experts armed with both traditional archaeology tools and cutting-edge technology are peeling back layers of earth to reveal untold stories of the final clash of the Jacobite Rising in 1746, as Judy Vickers explains.

For hundreds, possibly thousands, of years Drummossie Moor was just a wind-swept, boggy moorland east of Inverness, used by nearby farmers for grazing their animals. Flints uncovered in archaeological digs in the area show that folk had been around the moor for at least 4,000 years but its history was fairly unexceptional until one bloody hour on an April day almost 280 years ago.

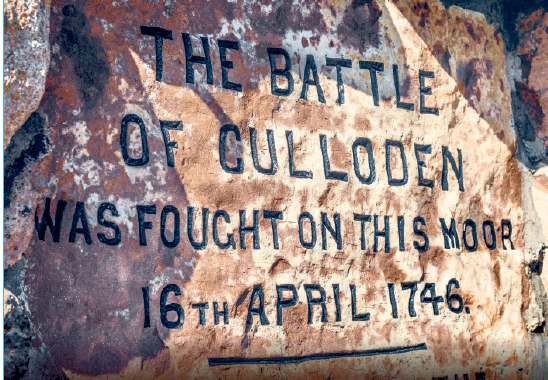

The Battle of Culloden in 1746 finally snuffed out the Jacobite cause – those who wished to restore the Stuart dynasty to the British throne – and put an end to more than 50 years of sporadic risings and rebellions. The battle, the last on British soil, was as brutal as it was short – one of the Government officers described it as “a general carnage” and said his men were splashing through the blood that covered the moor. Around 1,250 Jacobites were killed, the same number were wounded and 376 were taken prisoner – Government losses were just 50 with under 300 wounded.

The battle has become iconic for more than just its pivotal role in British political history, securing the protestant Hanoverian family on the throne. The romantic figure of Bonnie Prince Charlie who led the Jacobite army to a series of victories after he landed on Scottish soil in 1745 and raised his standard at Glenfinnan, his dramatic reversal of fortune at Culloden, his escape from the clutches of government forces after the battle and the brutal suppression of the Highland way of life in the days and years following have all helped to make this Scotland’s most famous battle

The battlefield is still giving up its secrets

Yet despite that spotlight, centuries on, the battlefield is still giving up its secrets. This October sees the fifth successive year of archaeological fieldwork and investigations at Culloden – and there will be open days with guided tours for members of the public to see the work going on and learn about what has been uncovered in previous years. This year’s dig will be again led by the National Trust for Scotland’s head of archaeology Derek Alexander, who explained: “This year we are looking for archaeological artefacts in the area to the north of the memorial cairn. This is an area where very little investigation has been undertaken before and was previously covered in a conifer plantation, which may have had an impact on the preservation of metal artefacts in this area. So, if we recover a similar number of artefacts to that found elsewhere we will be very excited.”

Those finds elsewhere include a large number of musket balls and grapeshot in a small 60 sq m area close to the Government frontline, vividly illustrating the intensity of the fighting on the Jacobite right wing and allowing battlefield experts to refine their understanding of the battle. “They have given a very detailed insight into the location of the hand to hand combat and have provided material evidence for the brutal nature of 18th century warfare” explains Derek.

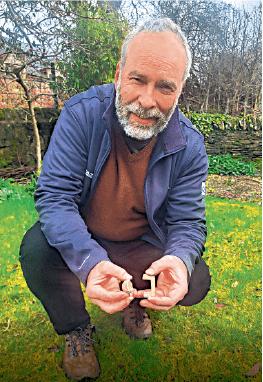

The most significant find – so far – was a shoe buckle believed to have belonged to Donald Cameron of Lochiel, who led the 400-strong Camerons regiment into the battle. A single piece of heavy lead grape shot, with a flattened side showing it had hit something with great force, and a highly decorated broken copper alloy buckle were found close to each other, just a few metres from the British Army frontline.

The finds fits perfectly with the story of the man known as “The Gentle Lochiel” that he was just drawing his sword as he reached the Redcoats’ frontline when he fell, wounded with grapeshot in both ankles. Lochiel, a leading Jacobite, survived Culloden and escaped to France with the prince. He was just one of many Jacobite casualties at the battle; Bonnie Prince Charlie’s forces, already hungry and tired, had been further exhausted by a night-time march to spring a surprise attack on the sleeping government troops.

That attack had been aborted and the weary troops had headed back to face a well-fed, well-equipped enemy in good spirits on the morning of April 16. Even the famed Highland charge was ably countered by the Duke of Cumberland’s soldiers who had been practising a counter-attack with bayonets.

The moor’s chequered history

Part of the reason for the wealth of material still being uncovered at Culloden – the battle takes its name from a small village a few miles from the actual field – is the moor’s chequered history in the years following 1746. Farmland began to encroach around the edges, plantations of spruce trees were created and in 1835 a road was built right through the middle of the site. The open moorland of the battlefield was lost.

By the 1800s visitors beyond just friends and family of the fallen were arriving and interest in the site for its memorial and historical rather than commercial significance grew. Duncan Forbes, the laird of Culloden who owned the site, created the memorial cairn and put up headstones to mark the clan graves in the 1880s, and the Gaelic Society of Inverness raised funds to repair the thatched roofs of two old cottages on the battlefield, King’s Stables Cottage to the west and Leanach Cottage to the east.

But not all the tourist attention was beneficial – in the 1930s a tearoom and petrol pump were erected in the middle of the battlefield to serve the rising visitor numbers.

In 1937, the recently formed National Trust for Scotland was given its first two small parcels of the battlefield and slowly, over the decades, acquired more of the land. But it was only in the 1970s that the old tearoom was bought and demolished and the 1980s when the road was moved and the forestry felled, meaning visitors could again see the moor the way the combatants did back in 1746. As the site was opened up, more was learned about the battle – and in fact he NTS’s own 1970s’ visitor centre was discovered to have been built on the second line of the government army. A new, relocated centre was opened in 2007.

Even archaeologists’ views on the shape of the battlefield has changed in recent years with experts now believing that it stretched over a wider area than previously thought. As Derek says: “There is always more to learn about what happened on the day of the battle.”

This year’s dig takes place from 12-18 October. For more information, visit www.nts.org.uk

All images courtesy of the the National Trust for Scotland, unless noted otherwise.

Main photo: Culloden Battlefield the final Jacobite Rising. Photo: VisitScotland/Kenny Lam.