By: Dr Wade King

The song Loch Lomond is well-known by Scots. Most of us learnt it as children. The lyrics are not immediately clear; it is a lament about “me and my true love” but it does not say who they were. The story behind the song is true. “Me and my true love” were Robert King and his wife Janet Kissock who lived in Renfrewshire from 1673 to 1746. They courted in 1698 – 1700 and married in 1700, to be parted by his death 46 years later.

Robert King’s baptism was recorded on 3rd January 1673 in the Old Parish Registers of the parish of Kilbarchan [ref. O.P.R. 568/1053 Kilbarchan] as “Robert son lawful to James King and Agnes Ffairy”. His parents were from the Dudwick estate at Ellon in Aberdeenshire. They had to leave Dudwick because they belonged to the Scots Episcopalian church, were Tory by political persuasion and their families had supported King Charles I in the Civil Wars of 1638-1649. The King family of Ellon were attainted specifically by a 1644 Act of the Scots Covenanter (anti-Royalist) parliament because General James King, Lord Ythan, had led the Royalist army centre at the Battle of Marston Moor in 1644. Also in that Royalist army were James’s brothers William and John, sons of the King family of Barra in the Garioch district of Aberdeenshire. That William King was the grandfather of James King who married Agnes Ffairy.

In 1652 Cromwell led an English army into Aberdeenshire to kill Royalists or drive them from their lands. James King and Agnes Ffairy fled before Cromwell’s forces. With other Episcopalians and Tories, they moved south to Renfrewshire, a Whig area where Cromwell would be unlikely to seek them. Many settled around Paisley, near Glasgow. The local Presbyterians were generous in letting them worship in one of the side chapels of the Abbey in Paisley. This was named the Non-Conformist Chapel to disguise its congregation. The Episcopalian families recorded their baptisms and marriages in the Old Parish Registers there for generations. These Episcopalian records were thought by genealogists to be lost until a few years ago, when the current author discovered them hidden in plain sight in the Abbey registers.

Robert King grew up on the family farm in Kilbarchan with his father James King, his mother Agnes Ffairy, his younger brothers William and James, and his younger sister Janet. Robert is recorded as attending Kilbarchan Kirk on 30th June 1686. Members of the extended King family lived around the Clyde, with other Episcopalian families that had sought refuge in the 1650s. In childhood, the King children roamed the farmlands along the Clyde and later the hilly country north of the river, out to the Highland hills around Loch Lomond, where the boys hunted the wild red deer.

Janet Kissock

Janet Kissock was born around 1680 but no record of her birth has been found. She was the daughter of George Kissock of Cumnock in Ayreshire. He later moved his family to Auchinleck in Ayreshire.

In 1698 Robert King met and became enamoured of Janet Kissock. In 1699 Robert aged 26 and Janet about 19 were courting as “true loves”, roaming in the gloaming along the River Clyde and the bonnie banks of Loch Lomond. They married in her family church in Auchinleck on 20th August 1700. They lived in Cumnock, Ayreshire and later in Beith, Renfrewshire, where Robert developed a farm and a mill. They had three sons, George born 1702, William born 1705 and James born 1707, and a daughter Janet born 1709.

Politics in Scotland became polarised between the Whigs in power in Edinburgh, supported by the Hanoverian government in London, and the Jacobites wanting restoration of a Stuart King, “the King over the water”, James VIII of Scots. In 1715 came the first major Jacobite rising, “the Fifteen”. Robert was a Tory, a Royalist and a Jacobite, like all his family, so he took his weapons and went to join the Jacobite army raised by John, Earl of Mar. Robert was then aged 42. He enlisted in Mar’s army and fought in the Battle of Sheriffmuir on 13th November 1715. The battle was indecisive and the surviving Jacobites retired. Robert went home to Beith and his soulmate, Janet Kissock.

Meanwhile, King James VIII’s son Charles Edward Stuart, remembered as Bonnie Prince Charlie, campaigned in France for a Stuart restoration. He pressed King Louis XV of France for financial and military support.

In 1745, Prince Charlie landed in western Scotland, raised his banner at Glenfinnan and declared he had come to reclaim his father’s throne. Robert, then aged 72, took his weapons and joined the Prince’s cause, enlisting in the Atholl Brigade being raised at Blair Atholl by Lord George Murray. Because of his experience, Robert was appointed the Brigade’s (only) Sergeant, or Training Officer. As such he taught the three battalions of the Atholl Brigade battle tactics, especially the Highland Charge, which involved a lot more than is commonly thought. Robert taught the clansmen to run forward, brandishing their weapons and shouting warlike slogans, until they were 20 feet from the Sassenach (English) line, then fire their muskets and pistols at the English, throw those weapons as hard as they could to injure the Sassenachs, then drop down as the English returned fire over them. Then, when the Sassenachs were reloading, Robert would shout the order for the Atholls to stand up, form wedges and hack into the Sassenachs with their broadswords and dirks.

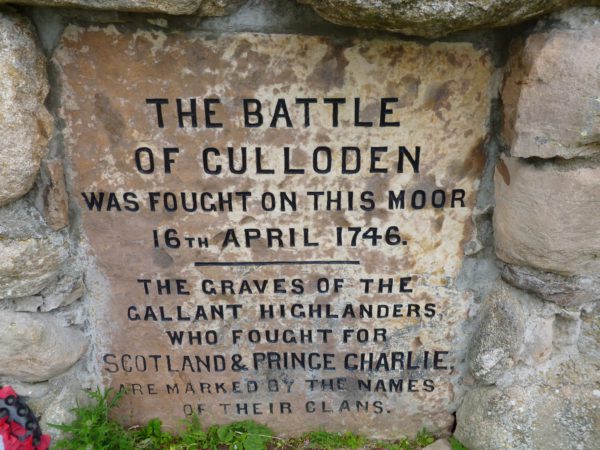

Culloden

Robert is listed in the muster roll of the Prince’s army as King but he took the nom-de-guerre of MacRae, the maiden name of his first daughter-in-law, because the King family had started to grow wealthy again, running ships from Port Glasgow to the American colonies, and he feared if he was captured under his real name the English would take vengeance on the family business.

Robert led the Atholl Brigade in the charge at Prestonpans on 21st September 1745, when General Cope’s English army was routed by the Scots. Robert continued serving the Prince in the Jacobites’ march into England in late 1745, when they reached Derby, and then the return march to Scotland. Later, Robert led the Atholl Brigade in another highland charge at Falkirk Muir on 17th January 1746, when the Scots defeated the Sassenachs again. Things seemed to be going the Scots’ way until the English Prince William, Duke of Cumberland, led a large, heavily armed English and Hanoverian army into Scotland to suppress the Rising. The Scots and Hanoverian armies came together at Culloden moor just east of Inverness on 16th April 1746.

At Culloden, Cumberland declared he would give the Jacobites “No Quarter”. Prince Charlie’s generals argued about whether to fight that day and if so the best tactics. Lord George Murray ordered Robert to lead the Atholl Brigade onto the moor on the right wing, the position of honour, while the generals continued arguing.

Robert formed up the Atholl Brigade’s second battalion on the moor and took his position in the middle of the front rank. They stood for twenty minutes while the English artillery bombarded them. Finally, Lord George Murray gave the order to charge. Robert led the Atholl’s in a highland charge down the right side of the battlefield. First, the Atholls came under musket fire from treacherous Campbells hidden behind walls on their right. Then the Atholls came under volley fire from Wolfe’s English infantry drawn up perpendicular to the main Sassenach line, so as to pour musket fire into the attacking Scots from their right flank. Robert led the Atholls into Wolfe’s regiment, and they did great slaughter there. Then Robert led them on into Barrel’s and Munro’s regiments of the main English line, and the Atholls did great slaughter again, although at the expense of heavy Jacobite casualties.

Robert fought with his broadsword and dirk for forty minutes, no mean feat for a man of 73 years. When he realised the battle was going against the Scots, Robert led an orderly withdrawal and the Atholl Brigade, or what was left of it, left the battlefield in good order with pipes playing, then dispersed into the Highlands.

A love bond

After Culloden, redcoat Sassenachtroops scoured the Highlands to hunt out Jacobites. They ravaged and killed Highlanders, whether Jacobites or not, killed their livestock and burnt their dwellings. In July 1746 Robert was captured and taken to Carlisle Castle in northern England, where he was confined in the dungeons with about 200 other Jacobite prisoners-of-war.

The English feared another Jacobite rising and wanted to ensure there were not enough Highlanders to form another Jacobite army. Initially they decided to execute all Jacobite prisoners-of-war in their keeping, as they had done with the Scots wounded and captured at Culloden. However, they also wanted to reach a political settlement with the Scots, so they decided to execute one in ten of their Jacobite prisoners and let the others go free. Because of his age, 73 years, Robert volunteered to be one of those executed, so allowing a younger man to go home.

On 18th October 1746 Robert and nineteen other Jacobite prisoners-of-war were taken from Carlisle Castle to nearby Harraby Hill. There they were executed by the atrocious English way of killing “traitors”, being hung, drawn and quartered. After the appalling process, their heads were placed on spikes over the castle gateway and their quartered body parts were sent to be displayed in four distant locations in England.

Robert’s execution inspired the words of the folksong Loch Lomond. The young Jacobite whom Robert saved “took the high road” (that is, he walked home) and Robert “took the low road” (was killed) but Robert was “in Scotland” (in spirit) “afore ye” (before the younger man reached home); but “me and my true love (Janet Kissock) would never meet again on the bonnie, bonnie banks o’ Loch Lomond” where they had courted 46 years before.

Thus, Loch Lomond is a love song, about a love bond that lasted almost 50 years. It is also a lament, about the severing of that bond by the Sassenachs when Robert and Janet might have lived together for many more years. It is a lament too for the Highland culture crushed by the Sassenachs after Culloden in the bloody aftermath of the battle and then the devastating Highland Clearances.

The author is the five-greats grandson of Robert King who led the charge at Culloden. He is immensely proud to be of Scots heritage and, in a sense, a son of Culloden, and is profoundly moved whenever he hears the tune Loch Lomond.

What a interesting moving story about a song that most Scots know so well. Fascinating!

Thank you for sharing such a fascinating account. I’ve been to Culloden on a windy grey morning in October. It was bleak and sombre, and I’ll never forget it. Your ancestor seems a noble, selfless man of great strength and character. Little wonder you’re so proud. My ancestors (the Robertons) were tenant farmers not far from yours. I really do hope they somehow knew such honourable people as your Robert King.

Such a beautiful , yet heartbreaking story.

One of courage , loyalty and immense selflessness on behalf of Robert

A story of love, not only between two people , but a love of country and fellowman

Heard it was a McGregor song, perhaps it is or perhaps due to the King claimed McGregor Sept

Think more research is needed

A absolute beautiful story of one man’s bravery and love for his wife, country and fellow men. If we only had more people of the same statue in today’s world we would have more beautiful songs such as Bonnie Banks O Loch Lomond.

I have learnt to play this song s melody on nylon string guitar. The story shared here gives meaning to the song words – which meaning can inform my playing of the music.— Thank you

I can well understand why Janet loved Robert so well for his whole life. What a brave, selfless and amazing man he was! My father’s family came from the Crawford clan in Scotland, although he grew up in America as we did. One of the highlights of his life was visiting Scotland with my mother, seeing Crawford Castle and buying the Crawford tartan which we used to make kilts. This story makes me even prouder of my Scottish heritage!

Thank you Wade.

I recently did a tour of the west coast and our driver/guide told us, as I have just learnt, a small part of that story.

He couldn’t understand why people sang Loch Lomond with such gusto, when the story was so sad and depressing.

And he actually played a depressing version of the song.

Now I know to continue toe tapping and singing with gusto for love, loyalty, courage and Scotland.

You have boosted my love and connection for my ancestral home.

Again, Thank you. 😃

Please ensure all Scotland’s travel agents have a copy of your story so tourists are informed, rather than deflated.