Imagine someone described as a force of nature. Who do you conjure? Perhaps a daringly dressed, larger-than-life dynamo who is constantly the centre of everyone’s attention. Maybe an artist at the peak of their creative intensity, or someone completely unwavering in their single-minded pursuit of a goal against the odds. Or, how about a seemingly frail, elderly woman, walking alone as cold rain pours down who, in a gentle and calm voice, asks if you might share your shelter with her.

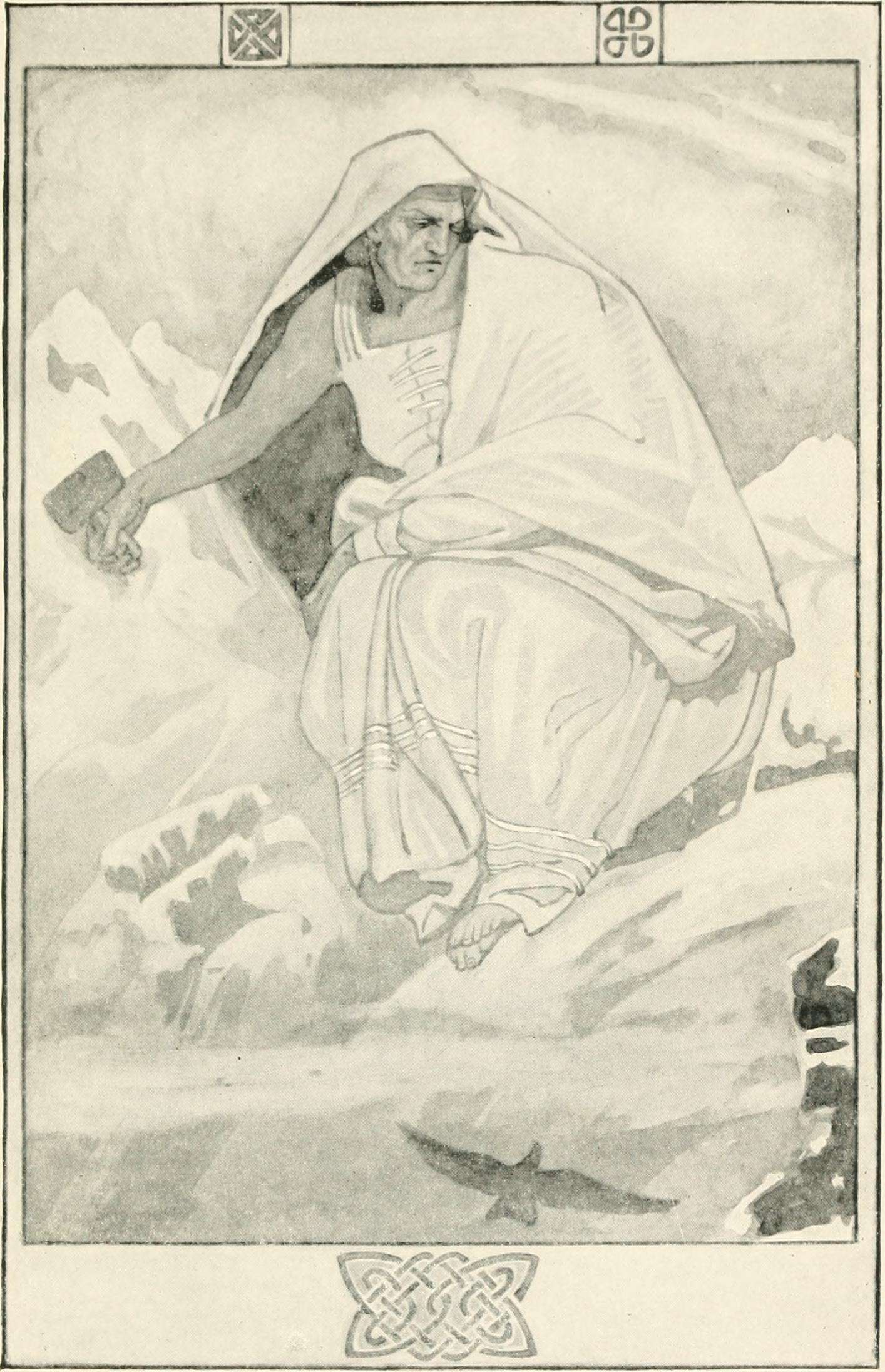

This unassuming woman is the Cailleach, not only a force of nature but the very embodiment of nature’s elemental cycles. To the Celts of Scotland, Ireland, and the Isle of Man, the Cailleach is a creation goddess who was here before even the hills and seas. There are many variations on her name’s meaning. Cailleach most directly translates to English as an “old woman”, but her name can also be interpreted as “veiled one” or “divine hag”.

Shaped Scotland

Indeed, the Cailleach shaped Scotland itself. The mountains and glens of the Highlands were made when, in giant form, she stomped across the land. The islands of Scotland’s west coast were rocks that fell out of the basket she carried on her back, with Ailsa Craig off the shores of Ayrshire once being a mere pebble that shook loose and fell through a hole in her apron.

The Corryvreckan in the Sound of Jura is the world’s third-largest whirlpool and is where the Cailleach washes her great plaid. When she hangs the plaid up to dry, ice crystals form upon it which then sweep across the land. This brings winter to Scotland, the season when the Cailleach is at her greatest power. When the Corryvreckan’s white foam surged to its highest point it was said that the Cailleach had ‘put on her kerchief’. Approaching the whirlpool in these conditions meant certain death.

In order to bring warmth and light back into the world, the Cailleach’s subjects must rebel against her wintery rule. They do this on the 1st of May, a vital turning point in the agricultural year, by holding fire festivals and preparing for the return of Angus and Bride, the king and queen of summer and plenty. Thus the Cailleach’s reign is ended, and she returns to slumbering in the upper reaches of sacred mountains like Ben Cruachan in Argyll, Beinn na Caillich in Skye, and Beinn a’ Bhric in Lochaber.

No one-trick goddess

Many flairs were added to the Cailleach’s repertoire over the centuries. Some versions depict the Cailleach riding a chariot pulled by huge black hounds, perhaps a memory of the Bronze Age and Iron Age when tribal elites rode across battlefields in chariots. Sometimes she hurls fireballs from her chariot, blasting stones apart with their power. Whatever the particular twist, the Cailleach was clearly no one-trick goddess: whether fire and ice or water and rock, all of the powers of nature are at her disposal.

Above all else it is a just balance of forces which the Cailleach seeks to instil in her subjects, both human and animal. Though she is a protector of wild things, she also encourages deer hunts when populations rise to the point of denuding the landscape of other forms of life. She is known to have given some young hunters the power of exceptional accuracy or good fortune. Some tales connect the Cailleach with the Fianna, the warrior-bards of ancient Ireland and Scotland including Ossian, Diarmad, and Fionn mac Cumhaill (Finn McCool), whose renown for hunting was unparalleled.

On the other hand, the Cailleach directly punished those who took too much. Poachers especially drew her wrath, but hunters who killed animals than they needed were also punished. The Cailleach would often send a deluge of water from the mountains to inundate the land which the offender lived on, ruining their crops and inflicting hardship for the winter ahead as the price of their greed. Similar judgments awaited those who, on encountering the Cailleach in the form of an old woman caught out in a storm, denied her their shelter, thus breaking the great taboo of ‘guest rite’.

The spectre of the Cailleach was used in social shaming when it came to the vital agricultural work required to sustain small, rural communities. The cutting of corn (meaning grains like barley and bere) took place in the autumn, and many communities across Scotland placed great importance on not leaving crops unharvested for too long. The first farmer in a district to finish cutting their corn made a little straw doll to represent the Cailleach. They passed the doll to their nearest neighbour, who in turn passed it to the next person to finish their harvest. The farmer who finished harvesting last of all was given the doll and expected to ‘feed’ it with some of his grain for the remainder of the year.

Belief

From the Iron Age through until the 19th century, belief in the Cailleach in the Highlands and Islands would have been nearly universal. Modernity, however, has taken its toll. As belief in the Cailleach has shrunk so, too, has the Cailleach herself, reduced now to the size of a garden fairy or teapot. There are some places, however, where the Cailleach still holds sway.

Deep in Glen Lyon is Tigh na Cailleach, the ‘house of the Cailleach’. There you’ll find a tiny shieling occupied by little stone figures barely larger than your fist. Every May Day (May 1st) these figures, representing the Cailleach, the Bodach (old man), and their family, are brought outside the shieling to face down the length of the glen. Glen Lyon, it should be noted, has long been central to the tales of the Fianna in Scotland. On Samhain (Halloween) the figures are placed inside for the winter.

The ritual movement of the figures at Tigh na Cailleach is believed to be the oldest Celtic ritual still practiced in its original form anywhere in Europe. The last named person to move the figures, local shepherd Bob Bissett, did so dutifully year after year. When he passed away, the people who took on the estate vowed to continue the practice. I am happy to confirm, by word of mouth from a recent visitor, that the figures are currently inside their shieling.

No doubt that come May Day in 2026, they will feel the touch of the sun and stand guard over Glen Lyon once more.

By: David C. Weinczok

Support the Scottish Banner! To donate to assist with production of our publication and website visit: The Scottish Banner