England was merry England, when

Old Christmas brought his sports again.

‘Twas Christmas broach’d the mightiest ale;

‘Twas Christmas told the merriest tale;

A Christmas gambol oft could cheer

The poor man’s heart through half the year.

A familiar scene, the over-the-top medieval English Christmas feast. We hear less about the traditional Scottish Christmas. Instead, we’re reminded that Christmas Day only became a public holiday here in 1958 and our preference was always for boozy celebrations at New Year. Of course, many Scots had Christmas Day off long before 1958 and, anyway, the Scottish contribution to Christmas tradition is greater than you might think.

Let’s look at that verse with which we started. Yes, it’s part of a jolly canto describing a rollicking medieval Christmas in a great English hall, but it’s from a Scottish verse epic, Sir Walter Scott’s Marmion (1808). As Scott describes, Scotland makes a contribution to the feasting:

Nor fail’d old Scotland to produce,

At such high tide, her savoury goose.

Then came the merry maskers in,

And carols roar’d with blithesome din…

Christmas traditions

Scott crams in Dickensian levels of detail to this scene; plum pudding (Scott calls it ‘plum porridge’), pies, carols, the boar’s head, roaring fires, bells and mistletoe. The passage influenced later writers about Christmas, not least Dickens himself. Scott certainly promoted Scottish culture, but he put in quite a shift for England too. As well as this picture of an English Christmas, remember how he re-invented the story of Robin Hood in Ivanhoe (1818)?

The American satirist Washington Irving published a spoof History of New York in 1809 which invented a number of traditions – Christmas stockings, Santa Claus travelling in a flying sleigh – that subsequently became part of Christmas. In 1817 he visited Scott at Abbotsford (they were fans of each other) and they must have chatted a bit about Christmas traditions while the log fire roared and the candles flickered. Irving, who had Scottish ancestry, went on to write more about Christmas; Old Christmas in 1819 described the festivities at the fictional Bracebridge Hall in England. Perhaps he’d discussed the Marmion frolics with Scott. Irving later met Dickens during the latter’s tour of America in 1841. Two years later, Dickens produced the immortal A Christmas Carol. I wonder what Irving and Dickens had talked about?

The composer Andrew Gant has written a couple of fascinating books about the origins of English Christmas carols; some of them prove to have more than a little Scottish influence. Gant writes of a book of songs entitled Cantus, Songs and Fancies which was published in Aberdeen in 1666 and credited to a John Forbes. In it there’s a sacred song with a peculiar mix of characters and images which gets even odder when we suddenly go to sea in a ship, and;

Our Lord harped, Our Lady sang

And all the bells of Heaven they rang

On Christ’s Sunday at morn

On Christ’s Sunday at Morn

By the mid-1800s, this song had evolved so that the number of ships had grown to three and ‘On Christ’s Sunday at morn’ was ‘On Christmas Day in the morning.’ Yes, a little-known Scot called John Forbes played a major part in the story of one of our best-loved carols.

Deck the Hall

And then there’s Deck the Hall (and, yes, it was originally ‘Hall’ not ‘Halls’); the jolly tune of this carol is Welsh and dates from the 18th century with no real link to Christmas. The first incarnation of the words we know today was written by Thomas Oliphant (1799-1873), a Scottish composer who was related to Lady Nairne, the famous writer of Jacobite songs. Oliphant had a distinguished career as a lyricist and Andrew Gant writes that ‘it seems a little sad that such an obviously interesting and accomplished figure is known to us today entirely for one, rather modest, lyric.’ And, omitting the ‘Fa-la-las’, this lyric runs;

Deck the hall with boughs of holly

‘Tis the season to be jolly

Fill the meadcup, drain the barrel

Troul the ancient Christmas carol!

In 1877 a somewhat stern American publication toned down the drinking references, and the third line became the faux-ancient ‘Don we now our gay apparel’. Over the years, too, ‘hall’ for some reason became ‘halls’.

And then there’s James Edgar. Who? Edgar was an Edinburgh man, born in 1843, who emigrated to the USA and set up Edgar’s Department Store in Brockton, Massachusetts. In December 1890, he had the idea of dressing up as Santa Claus and walking around the store in the run-up to Christmas. He never got as far as setting up a grotto and listening to children’s present requests, but if your children have ever pestered you because they want to see Santa in a department store, blame James Edgar.

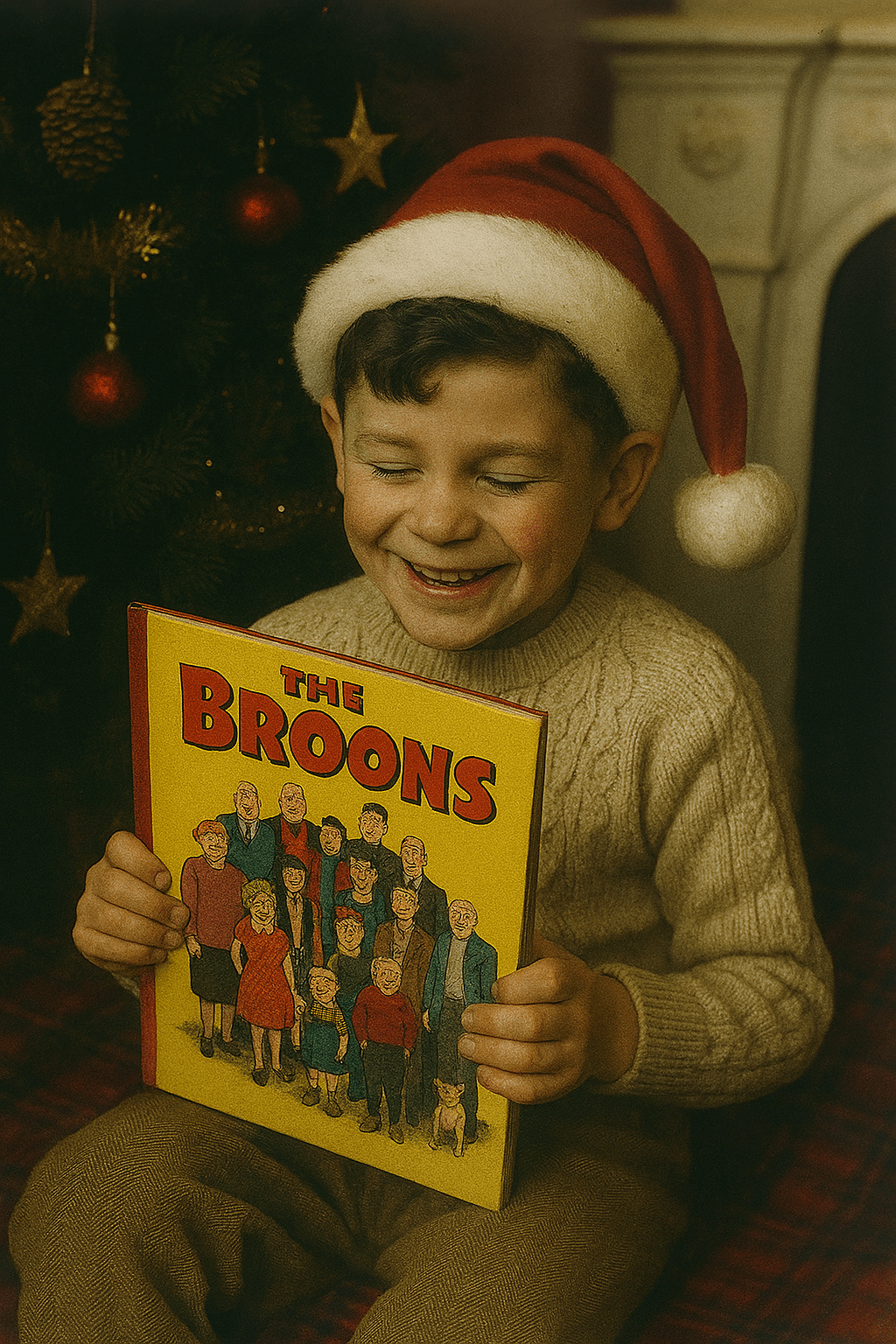

The annuals

And finally, Scotland’s greatest contribution to Christmas. What a thrill in the 1960s and 1970s to unwrap a present and find the ‘annual’ of your favourite comic; The Beano or perhaps The Dandy, The Victor or The Beezer. That glossy-covered hardback with the new-book smell that promised all the joys of your favourite comic, only much more!

These comics mostly began in the 1920s and 1930s and the best-known ones were published by the Dundee firm of DC Thomson and Co. The Dandy annual first appeared in 1939 with the first Beano annual the following year. These annuals spread far and wide but of particular interest in Scotland (and also popular in Northern England) were those collections of stories featuring Oor Wullie or The Broons, cartoon strips that appeared in DC Thomson’s Sunday Post newspaper. These were published in alternate years; Christmas was defined by whether it was a Broons year or an Oor Wullie year. The Broons Book first appeared in 1940; the Oor Wullie book, of course, debuted in 1941.

How Wullie and The Broons celebrated Christmas, New Year or Easter or Hallowe’en had a great influence on we youngsters who devoured the annuals. The Broons and Oor Wullie Christmas and New Year stories always came at the end of the book, as the stories followed the sweep of the year. In recent years, the books have departed from this model, with Christmas strips even appearing in the middle! I’m not happy about this.

Scotland, then, has contributed a surprising amount to wider Christmas traditions and you can still, if you want, look forward to Christmas morning curled up with the Beano annual or The Broons Book. Whatever age you are.

Support the Scottish Banner! To donate to assist with production of our publication and website visit: The Scottish Banner