Most conventional histories present the Norse invasions of Britain as a flash in the pan, an intense if fleeting period when the island’s kingdoms were carved up by seaborne raiders and their great axes. Bloody and swift as some raids were, in Scotland the picture is much more complex – there simply wouldn’t be a Scotland as we know it without centuries of Norse influence. So, where and when did Scotland’s ‘Viking Age’ begin and end, and what traces of it remain?

Fury of the Northmen

Immortalised in countless books, television shows, and history books, the Viking raid on Lindisfarne in northeast England in 793AD is commonly referred to as the very first appearance of the Northmen in Britain. We now know, however, that Vikings were plundering and setting down early roots in Shetland, Orkney, and the Outer Hebrides several decades before the ‘fury of the Northmen’ visited Lindisfarne.

The Northern Isles of Scotland are, after all, a mere two days’ sailing from northern Denmark or southwest Norway, barely a weekend trip for a Viking warband. Many Norse sagas mention raids in northern Scotland and the Hebrides as casually as we might mention going to the shops to buy groceries. There is evidence for Viking sea battles on Scottish shores as far south as Bute from the mid-780sAD, and no doubt some intrepid Norsemen ventured west significantly earlier than that.

Norse

One important thing to note is terminology. ‘Vikings’ were the raiders and plunderers who first struck British shores and did not intend to permanently settle upon them. Once they established communities and buried their dead in the new-won lands, they are referred to as ‘Norse’. The key difference is that ‘Viking’ is a verb, not a noun. There is no ‘Viking’ tribe or single culture. To go ‘a-Viking’ was to go raiding during the summer, so it really describes an occupation (raiding) rather than a cultural identity. A group of 9th century Norwegians, Swedes, and Danes would have had far more to fight over than to agree on, and they often did!

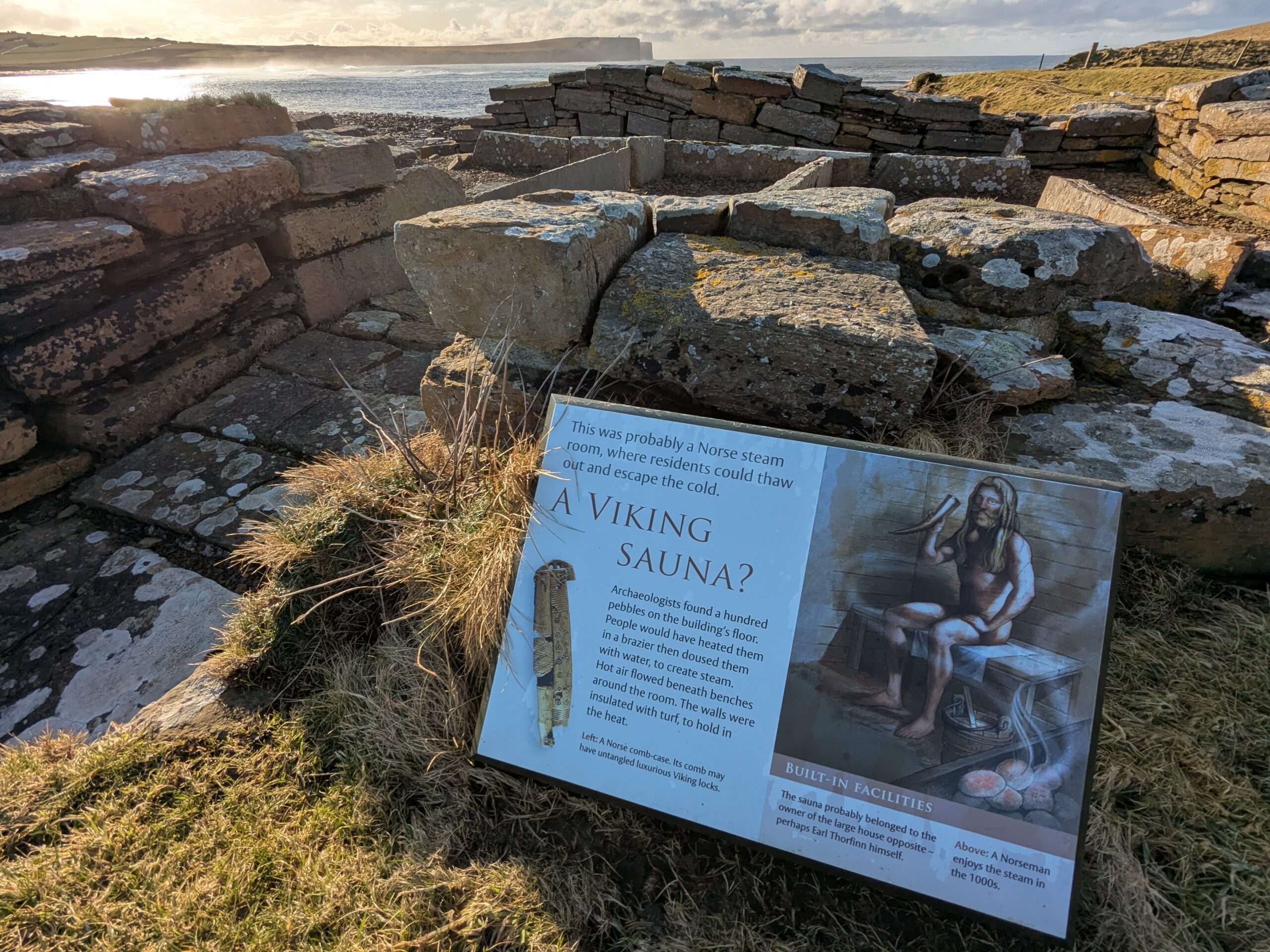

By the early 800s AD significant Norse settlements were founded in places like Birsay in Orkney and Stornoway in Lewis. At Westness in Rousay, Orkney, the earliest Norse settlers buried their dead alongside the Pictish dead in the local cemetery. Perhaps this was one way of stamping their ownership upon the land, or of symbolically declaring that they were the new locals. These earliest settlers were known as landnamsmen, the ‘land-taking men’.

Perhaps unexpectedly, they seem to have respected many existing monuments like the ancient chambered cairns, and many Norse families would have included people of mixed Norse and Pictish or, in the Outer Hebrides, Gaelic heritage. Indeed, the Outer Hebrides became known in Gaelic as Innse Gall, the ‘Isles of the Strangers’, and a hybrid Gall-Gael culture emerged in subsequent centuries along Scotland’s western seaboard. This culture survived well into the Middle Ages in the form of Somerled’s Kingdom of Argyll and the Isles.

Lochlannach

It’s from the 830sAD onwards that things got rather more dire for those living in Scotland. Iona, a shining seat of Celtic Christianity, was repeatedly sacked. In 839AD a Norse army destroyed an army of Picts and slew the kings of Fortriu (in the central Highlands) and Dál Riata (in Argyll). Ancient power centres like Dunadd were abandoned due to constant raids. In 870AD a Norse host under Ivar the Boneless besieged and sacked Dumbarton Rock, capital of the Strathclyde Britons. They carried hundreds off as slaves and any survivors fled to their kinsmen in Wales. Native strongholds and kingdoms fell like autumn leaves to the Norse, while Norse realms like the mighty Earldom of Orkney ascended and gobbled up the leftover pieces of the resultant power vacuum.

The 10th through 12th centuries saw these Norse realms continue to expand until checked by increasingly assertive kings of Scots, who made forays into the Isles and clawed back territories in the northern mainland. During this time Norse culture largely replaced Gaelic culture in the Western Isles, with many place names there today still containing Norse elements. Gaelic folklore reflects this, with many folk tales centred on Irish and Scottish heroes resisting the ‘Lochlannach’, men from across the eastern sea who assumed mythological proportions and powers.

Norse folklore also imprinted on the Scottish landscape. In Orkney and Shetland many large boulders are attributed to Norse giants throwing them at each other, and in the Outer Hebrides many of the ancient ruins of chambered cairns and brochs were attributed to supernaturally strong Norse builders. The Norse left hogback gravestones along the banks of the River Clyde, carved runes into standing stones at sites like the Ring of Brodgar, built longhouses from Shetland to Kintyre, stashed away or abandoned valuables like the Galloway Hoard and the famed Lewis chess pieces, and – slowly but steadily – began converting to Christianity.

Role in Scotland’s story

The height of Norse activity in Scotland may have been behind them by the 13th century, but pivotal events were still to unfold. In 1230 a Norse fleet assailed Rothesay Castle in Bute, temporarily wresting it away from its Stewart lords. In 1263, led by no less than the King of Norway himself, Håkon IV, a Norwegian army swept through the Isles and landed at Largs on the Ayrshire coast. Checked by a Scottish host, the Norse were forced to abandon their plans to retake the western seaboard and Håkon died in Kirkwall that December. This was to be the final military incursion of the Norse in Scotland.

However, it was not for another two centuries that, in 1472, Shetland and Orkney were pawned to Scotland by Norway and simply never purchased or taken back. Those archipelagos were part of the Norse world for over 600 years, longer than they have been part of modern Scotland and the UK. There are even whispers today of a desire for them to re-join Norway, and even a brief venture to them will instil a strong sense of how culturally intertwined the islands are with their Norse past.

Many people think of Scotland’s Viking and later Norse history as a brief, albeit bloody and dramatic, flash in the pan, and no doubt the victims of Viking raids and early Norse conquests are a testament to the brutality of the times. Zoom out, however, and we see a period of no less than four centuries when Norse armies, politics, material culture, folklore, and settlement patterns were central to the stories of huge swathes of Scotland. New discoveries emerge from soils and shorelines every year which shed further light on their role in Scotland’s story – and with any luck, someone walking on a storm-swept beach this winter might just happen across another long-lost piece of the puzzle.

Text and photos: David C. Weinczok

Main photo: Norse ruins at Birsay, Orkney, including a possible sauna. © David C. Weinczok.

Support the Scottish Banner! To donate to assist with production of our publication and website visit: The Scottish Banner