This month a 90-year-old silent film shot in Shetland is being shown as part of The Hippodrome Silent Film Festival, Scotland’s only festival of silent film. The Rugged Island was made by the pioneering Scottish female filmmaker Jenny Gilbertson about crofting families and life in Shetland. This piece of historic Scottish cinema, which includes new commissioned music played and composed by Shetland people, will be livestreamed so anyone interested globally can see it, as Judy Vickers explains.

She was the middle-class, university educated daughter of a well-off merchant who left city life in Glasgow behind to become a pioneering documentary maker on the bleak, windswept crofts of Shetland in the 1930s. Now, 90 years on, Jenny Gilbertson’s only drama film is being showcased once more – shining a light on both those who eked out a way of life in tough conditions and the remarkable story of the woman herself. The Rugged Island: A Shetland Lyric is being shown this month at the Hippodrome cinema in Bo’ness, on the banks of the Forth, as part of its annual silent film festival – and is also being livestreamed worldwide with a newly commissioned score from Fair Isle multi-instrumentalist and composer Inge Thomson and Shetland-born musician Catriona MacDonald.

The realities of Shetland at the time

The 1933 film was made single-handedly by Gilbertson, who wrote, shot and edited the 56-minute movie with a cast of mainly locals – there was only one professional actor, Enga Stout. It tells the tale of a young couple facing a dilemma; whether to take up the invitation of her uncle to join him on his farm in Australia or to stay and work the family croft in the land of their birth. The Rugged Island was not the first film Gilbertson had shot on Shetland – she had also made a series of short documentaries where she developed her quiet observational style and endeared herself to the locals who took the Glaswegian to their hearts.

Gilbertson, nee Brown, had been born in 1902 in the city where her father was an iron and steel merchant. With his backing, she studied at Glasgow University, then headed to London for a secretarial course in 1929. The typing and shorthand took a back seat, however, after she saw a screening of a film about Loch Lomond; inspired to become a film-maker herself, she bought a 16mm camera, headed up to Shetland, where the family had taken summer holidays, and made her first film, a documentary following a year in the life of the island and its inhabitants. That film, A Crofter’s Life in Shetland, made in 1931, shows the men and women of the island carrying out their everyday tasks of digging peat, planting potatoes, knitting and fishing. “She spent a lot of time with people, getting to know them and really getting into the rhythm of their lives. Her filming was very natural. That’s what makes it so exquisite,” says Shona Main, a film-maker based in Shetland and a researcher into Gilbertson’s life.

On its premiere in Edinburgh, it caught the eye of “the father of British and Canadian documentary making” John Grierson, who was effusive in his praise, saying she had “broken through the curse of artificiality” and was “an illuminator of life and movement”. Perhaps as important as his encouragement was that he went to buy a series of her short films made on Shetland for the General Post Office Film Unit in London. Inspired by his mentorship, she bought a 35mm camera and headed back up to Shetland to make The Rugged Island, which although it was a fictional story still very much reflected the realities of Shetland at the time, from the scenery and the people to the crofting and the choice the couple in the movie face.

Crofting life

Emigration from Scotland had built during the years of the Clearances in the 19th century and hit its peak in the 1920s when it is estimated around a fifth of the working population left the country, many on ships sailing from the Clyde to Canada, New Zealand, Australia, South Africa and the United States – although ironically in the 1930s, when Gilbertson was filming, there was a surge in people coming back as the worldwide economic downturn took hold. And the record it shows of crofting life at the time is also hugely important, says Donna Smith, chief executive of the Scottish Crofting Federation. “Crofting is an integral part of the culture in the Highlands and Islands, it is a social heritage thing, not just economic,” she says. Modern crofting emerged from the Clearances of the 17th and 18th century, when landlords evicted tenants from their land to create large pastures for more economically profitable sheep but it also left vast areas depopulated. It was only at the end of the 19th century that new laws stopped this.

“The 1886 Crofting Act gave crofts a clear status, tenants were given absolute security of tenure and the Act gave them the right to a fair rent,” says Donna. “There are a lot of crofts which were registered in 1886 which are still in the same family because the Act gave tenants the right to pass the croft on. There are duties attached to a croft, including living within a certain area and looking after the croft. A croft is a smallholding with a home built on it and common grazing rights, usually on a nearby open hillside. Crofts were deliberately created to be small, they were never about making money, it’s about keeping people in the rural townships. Some people make all their living from crofts but many also have other jobs.” Today those other jobs (there are just under 3,500 crofts on Shetland now, a number which has not changed significantly since Gilbertson’s day) can include holiday accommodation; in the 1930s they were more likely to be knitting for the women and herring fishing for the men. “People might think why put in all the hard work on the land when it doesn’t make enough to live on, but it’s not about the money, it’s about the stewardship and management of the land. A lot of places would not be populated if it wasn’t for crofting. It’s a massive part of Scotland’s history,” says Donna.

One of the pioneers of female film-making

And Gilbertson’s films perfectly captured this sentiment and sense of belonging without being over-romantic, says Shona. “It’s not the overblown kind of film we think of when we think of silent films because it’s something rooted in reality,” says Shona. “She was an extraordinary film-maker because of the time she took and the very careful looking and listening. It was a particular time before the oil, before life changed and people lived incredibly frugal lives but they are not shown as victims, they are not romanticised.” Shetland became her home after she married her leading man from The Rugged Island, Shetland farmer Johnny Gilbertson and became a mother of two girls, to an outsider perhaps a strange move for a city girl. But Shona says: “I think she found middle class Glasgow stifling. All those balls, and bridge and golf. She wanted connection and friendship – and that’s what she got and then attended to, both in Shetland then later in the Canadian Arctic.”

But times were changing. Talking pictures had become all the rage and in a bid to make her film more up-to-date and appealing to cinema audiences, she sank £100 of her own money to commission a score to accompany it – “a fantastic amount at that time,” says Shona. It means that there is both a silent and sound version of the film but unfortunately for Gilbertson, while the movie was a success, her distribution company had gone bust and she never saw a penny back on her investment. “It then becomes incredibly expensive to make a film, war arrives and Johnny goes to war and there was no money at that time so she has to give up film-making,” says Shona.

She spends the next 30 years as a teacher, mother and wife in Hillswick in Shetland but her career as a film-maker has an unusual post-script. After retiring in 1967 and the death of her husband, she takes her craft up again, this time across the Atlantic. She goes out to Coral Harbour in Hudson Bay to film life in an Inuit settlement. “She spent nine years out there, making extensive films and building long-term relationships with the people there,” says Shona. Well into her 70s she was still making films, including for the BBC and the Canadian Broadcasting Company (CBC), once travelling 900 miles north of the Arctic Circle at the age of 76 to make Jenny’s Arctic Diary, her films still showing the gentle intuitive touch of her Shetland creations. One of the pioneers of independent, female and documentary film-making, she died in 1990.

The Rugged Island: A Shetland Lyric will be screened as part of HippFest at the Bo’ness Hippodrome on Wednesday 20 March and will be livestreamed online via HippFest at Home, www.hippodromecinema.co.uk/silent-film-festival.

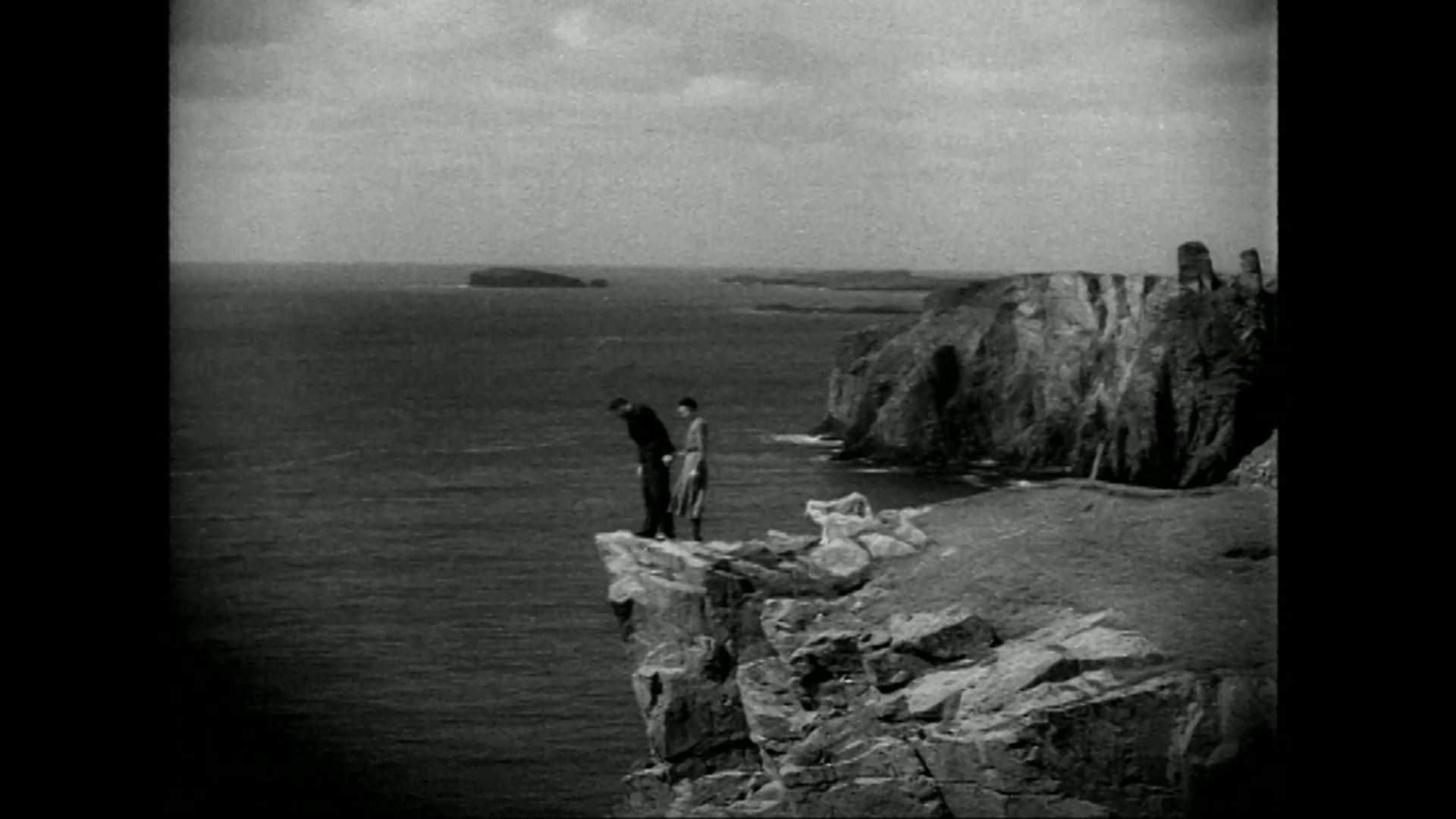

Main photo: The dramatic Shetland cliffs provide a background for action in The Rugged Island.