By: Eric Bryan

The Glasgow tractor changed Scottish farming life in the early 20th century and was the only tractor designed and built in Scotland. Production of this special tractor lasted just five years but still to this date remains Scotland’s only indigenous tractor, built for Scottish conditions, as Eric Bryan explains.

In the early 20th century, imported mass-produced American-made farm tractors dominated the market in Britain. But these tractors were designed mainly to work the vast flatlands of the American Midwest, and weren’t ideally suited to operating on hilly and muddy Scottish farmlands. With an eye toward creating a tractor fitted for working in such British conditions, W Guthrie, in conjunction with John Wallace & Sons Farm Implements and the DL Motor Manufacturing Co of Motherwell, designed the Glasgow Tractor.

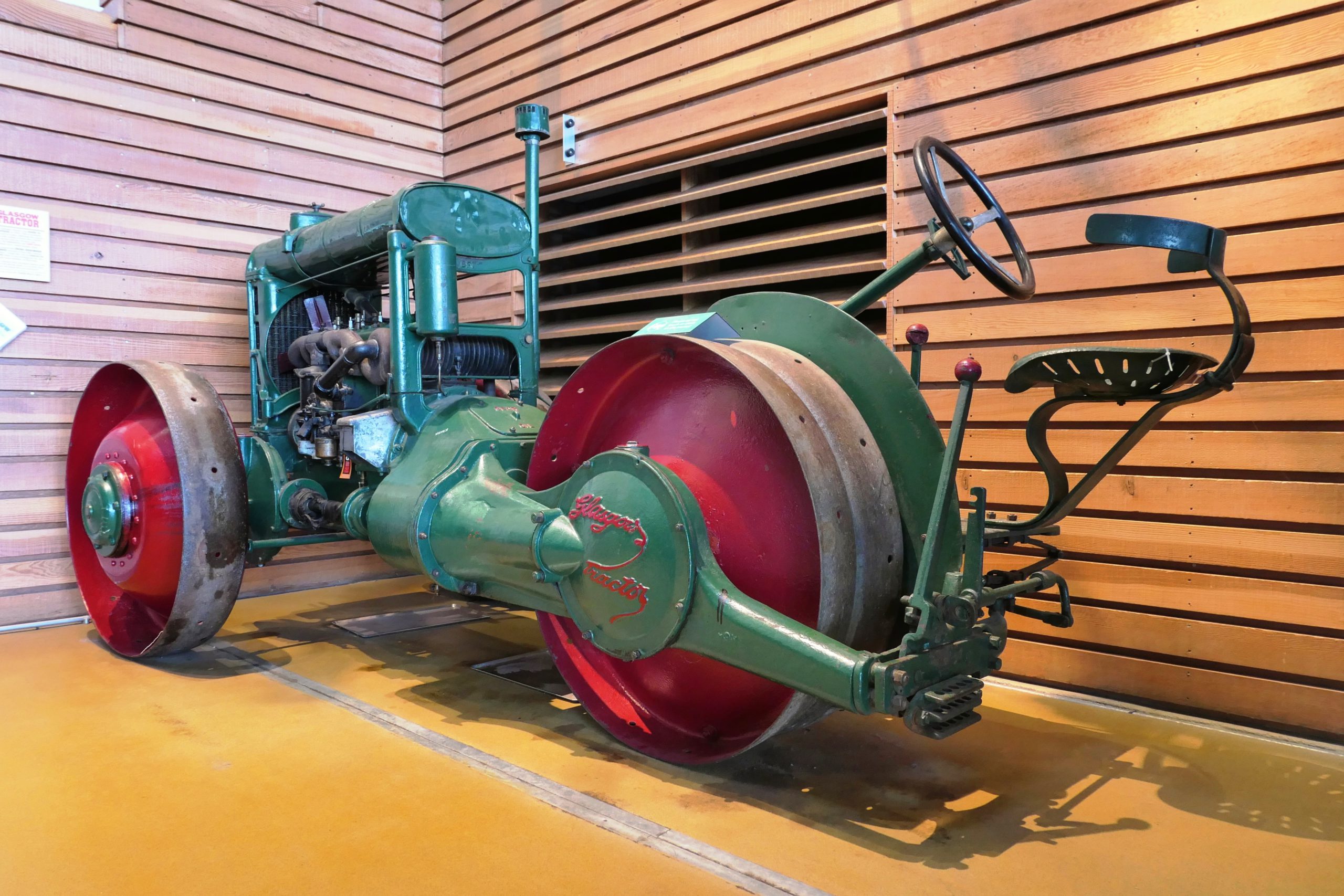

Drawn up specifically to be compatible with Scotland’s challenging terrain, the Glasgow was not only an all-wheel drive tractor, but was in a three-wheeled configuration – not as you’d expect with two wheels in the back and one in front as with a crop-row tractor, but with two in the front and one in the back. This layout, combined with its weight distribution and low centre of gravity made the tractor resistant to overturning. The three-wheeled AWD system offered more stability than did a four-wheeled configuration, as it was less likely that one of the wheels would lift clear of the ground on steep or awkward landscapes. As a Glasgow advertisement stated, ‘The secret of the “Glasgow’s” splendid work on steep gradients is its three-wheel drive.’

Improved traction

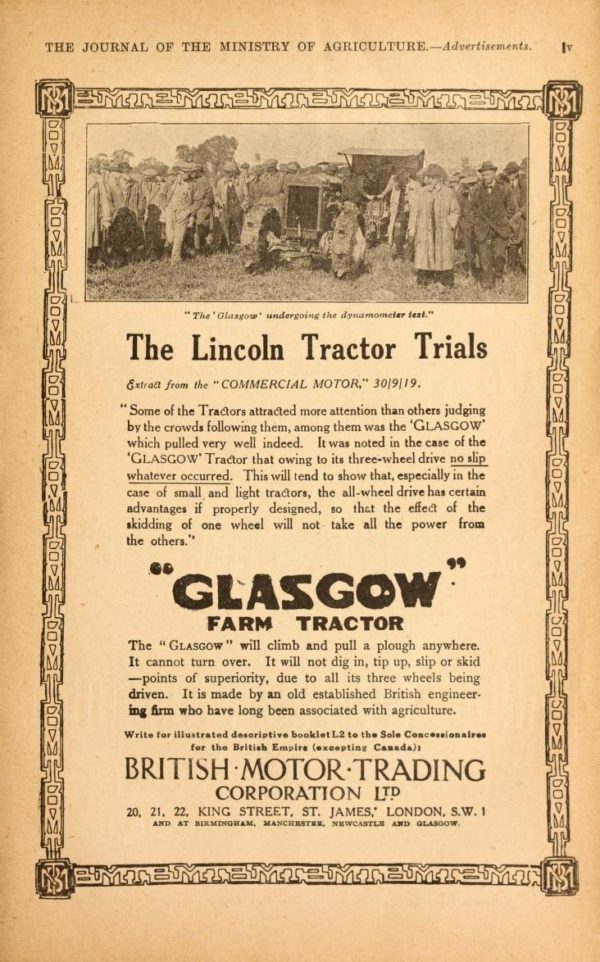

Each of the Glasgow’s wheels could be fitted with spuds for improved traction, while the machine’s even weight distribution reduced bogging. The tractor’s AWD, with all wheels powered and turning cooperatively, meant that if one wheel slipped in a rut or got stuck against an obstacle, the other wheels kept turning and helped to free the slipping or trapped wheel. More Glasgow advertising somewhat sensationally claimed, ‘The “Glasgow” will climb and pull a plough anywhere. It cannot turn over. It will not dig in, tip up, slip or skid – points of superiority, due to all its three wheels being driven.’

The Glasgow’s steering system, rather than turning the rear or front wheels, slowed one of the front wheels while the other wheels kept rotating at a consistent speed, causing the vehicle to pivot on the slowed wheel and so turn the tractor. The driver’s iron basket seat was positioned all the way at the back of the machine, behind the rear wheel. From this perch, the operator had a full view of the front wheels as well as of the hitching and lift mechanisms which were positioned below the seat.

The Scottish tractor

Debuting at the 1919 Lincoln Tractor Trials, the Glasgow made a strong and favourable impression. At this gathering, W Guthrie drove the tractor up a 1 in 7 grade and pulling four 12 x 10 inch ploughs which usually required four horses to drag, ploughed one acre per hour. The Commercial Motor reported that the Glasgow attracted much interest at the trials, and pulled impressively. ‘It was noted that in the case of the “Glasgow” Tractor that owing to its three-wheel drive no slip whatever occurred. This will tend to show that, especially in the case of small and light tractors, the all-wheel drive has certain advantages if properly designed, so that the effect of the skidding of one wheel will not take all the power from the others.’

The Scottish tractor had an American Waukesha four-cylinder 27 horsepower engine, two forward and one reverse gear powered via nickel steel reduction gears, a Zephyr carburettor, and weighed 1636kg unladen. Its dimensions were 3.4m long, 1.7m wide and 1.9m high. Despite its promising start, the Glasgow Tractor was to face some daunting challenges. While the 1922 price tag for the Glasgow stood at £375 (and would swell to £450), the Fordson Tractor then available cost only £120. The Glasgow was also overwhelmingly noisy for the operator, and its motor proved to be a high maintenance unit. This combination of factors led to the demise of the Glasgow, then Scotland’s sole home-grown tractor, in 1924.

The National Museum of Rural Life

A surviving example of the Glasgow Tractor is on display at the National Museum of Rural Life, near East Kilbride in South Lanarkshire. Operated by National Museums Scotland, the Museum of Rural Life is sited at Wester Kittochside Farm and opened in 2001. The museum carries on and expands upon the collections and work done by the former Scottish Agricultural Museum, which was established in 1949 and based at Ingliston. The museum comprises the main building and visitor centre, Georgian farm buildings, and surrounding agricultural fields and hedgerows.

Scotland’s largest collection of combine harvesters, tractors and other agricultural machinery are housed at the museum. Indoor and outdoor exhibits present tractors from most decades of the 20th century. Besides the Glasgow, other tractors in the collection are Fordsons, a Ferguson Brown, Ford Ferguson, David Brown, Field Marshall, and a Ferguson ‘Little Grey Fergie’. A modern Deutz tractor pulls the Farm Explorer which carries visitors to the farm. Wester Kittochside Farm is a working farm, and resident animals include Clydesdale horses; Tamworth pigs; Aberdeen Angus, Ayrshire and Highland cattle; sheep, hens and farm cats. Farm buildings visitors can explore are the Georgian farmhouse, bothy, small byre, stables, gig shed, threshing barn, dairy, milking byre, hay shed, Dutch barn, hen house, sheep pens, pig sty, and pig run.

Main photo: Glasgow Tractor on display at the National Museum of Rural Life, East Kilbride. Photo: Magnus Hagdorn, CC BY-SA 2.0.